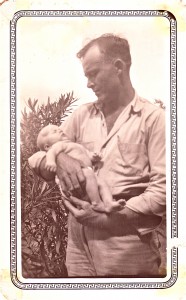

Picture a man’s man with a heart that melts for his wife and children, unshakeable faith in God, and rock-solid integrity.

That’s Ella’s father, the character Gavin McFarland in The Calling of Ella McFarland.

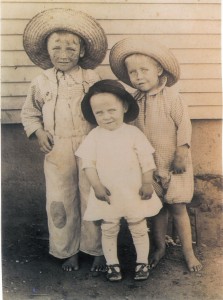

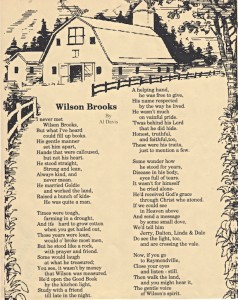

And my father, Wilson Freeman Brooks.

Each man migrated from the place of his birth to a land that promised something better–Gavin McFarland, from the Ozark Mountains to Indian Territory where farm land was available for lease through the Chickasaw Nation’s permit system; and my father from Silverton on the High Plains of Texas to the Lower Rio Grande Valley of Texas where farm land was so fertile it was known as the Land of Milk and Honey.

Each was reared on hard-scrabble soil, sons of dirt-poor farmers.

Each paced the floors when their crops were hailed out or a drought choked the land … when boll weevils devastated the cotton … when freezes took their crops … and when farm prices plummeted.

Each saw that his family knew God, feared Him, worshipped Him, and served Him.

Each learned to pitch and lead hymns using shape notes and taught his sons to do the same.

to do the same.

Each studied the Bible with friends around the kitchen table.

Each started out with nothing and made something of himself.

Each showed his daughter what the love of God looks and feels like. Gavin McFarland, like my father many times over, gave glimpses into God’s love through his love for his children.

A personal incident in 1967 illustrates this reality in my life …

In 1961 Daddy was stricken by a mysterious malady in which the muscles of his body atrophied–starting in one shoulder, then the other, down both arms, into his legs, and eventually his torso. Multiple examinations, lab tests, and exploratory surgeries in multiple medical complexes across the country, ending eventually at Mayo Clinic yielded no diagnosis. Daddy suffered from an as-yet-undiagnosable condition that in 1971 took his life–after ten years of losing strength cell by cell, muscle by muscle, organ by organ until his heart gave out.

Daddy’s ability to function independently deteriorated with his body. Driving, for example. As a farmer, he was accustomed to jumping into his pick-up and traveling in a dust cloud down unpaved roads from field to field–some of which were scattered miles apart–not thinking twice about the ease with which he did so–until he couldn’t. Somehow with just his hands in his lap, he was able to drive Mother’s car with power steering just on the farm roads. He did so as long as he could, but in time, one farm worker was designated to drive him “to and from the fields.”

I attended college 500 miles away from home–at Abilene Christian University in Abilene, Texas from 1964-68. Daddy did his best to see that I  was able to take everything I thought I needed to live away from home, even if it required hitching a trailer to a car he couldn’t drive. He couldn’t even lift his arms.

was able to take everything I thought I needed to live away from home, even if it required hitching a trailer to a car he couldn’t drive. He couldn’t even lift his arms.

Our dorm had no telephones in rooms. Instead, we girls learned to share a pay phone. One evening during my weekly call home, I told Mother and Daddy about some incident that had left me feeling discouraged–blue as Mother would have said. I thought little about the effect my experience might have on my parents, how they might have shared my emotions and longed to make it better. I only knew it was good for my soul to tell them, and, without fail, I felt better for having done so.

The following day I received a “buzz” in my room–the ancient communication system whereby a receptionist at the front desk let us know we had “callers.” I skipped downstairs expecting to find my latest date but found, instead, my crippled father in a simple cotton shirt from Sears sitting in a room full of robust, properly-attired, coiffed, and cologned young men.

“What are you doing here? Where’s Mother?” I said, looking around.

“She’s at home. I came by myself.”

“Alone!? You drove 500 miles alone? Why?”

He looked down, as he often did when he was gathering his thoughts. “Last night on the phone … you sounded low … like you needed me.”

“But what if something had happened … a wreck … what if …? You … Mother should’ve–“

“No, babe, I wanted to do this for you–just me.”

I knew Daddy’s was an act of love and self-sacrifice, his gift to me. But it was some years later when I realized his gift was a picture of my Heavenly Father’s love for me–His gift of grace through the giving of His Son Jesus … and of Jesus’ sacrificial act in leaving the comforts of home to make an arduous journey to reach out to God’s children who were hurting.

Without a thought for himself, Daddy would have died for his children.

Gavin McFarland would have done the same.

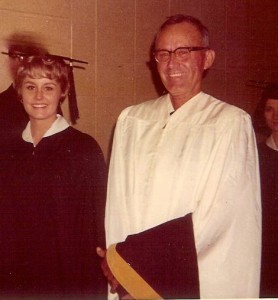

P.S. When I graduated from ACU in 1968, I asked Daddy to “hood” me.

“How can I? I can’t lift my arms,” he said.

“How can I? I can’t lift my arms,” he said.

Other parents would sit behind their children, stand, and slip the hood over the graduates’ heads. But Daddy couldn’t, so I devised a way: He held onto the hood, and I turned around and lifted his hands over my head.

My gift to him.